For schools to become spaces of healing and belonging

Today is not an officially significant date for Indigenous people in Brazil — and for that very reason, we’re choosing to talk about them. Specifically, about 18-year-old activist Carlos Ramos de Lima, of the Miranha Apurinã people, a member of the Youth Council of the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Initiative (CAMHI) Brazil, a committee where, according to him, it has been possible to research public policies and talk about the mental health of Indigenous and quilombola youth — quilombolas are descendants of enslaved Africans living in quilombos, settlements founded by escaped enslaved people in colonial Brazil.

When he spoke at the webinar “The social role of schools in promoting mental health” last November, Ramos advocated for respect for subjectivities, identities, and for everything Indigenous youth have to say about their own needs and desires. He insisted that schools must be anti-racist environments, and that the cultures of traditional communities should be treated without exoticism, without that feeling of exceptionalism typical of traditional civic celebrations such as the National Day of Indigenous Peoples.

“We don’t want to be objects of study on April 19. Our people, our history, and our knowledge exist year-round”, Ramos stated. Below are the most striking excerpts from his testimony.

True listening

“We learn from an early age that every piece of land is a territory — with culture, rules, history, and power. The school becomes a territory too. And like any territory, it can be a space of belonging and healing, or a space of silencing and sickness.

In the current view and structure of the school environment, care is often a passive concept: it’s the safe gate, the meal on the plate, the absence of physical violence. And ‘listening’ is simply having the principal’s office door open — even if we can only go in to make a complaint.

But for us — young people, activists, people who want agency — caring means having our subjectivity and identity valued and validated. It’s the teacher noticing that you’re not well and asking how you are — not just what you did. And listening is not only what the adult hears, but what they do with what they heard.

In other words, listening is when our opinion about the curriculum, about the rules, about the environment is taken seriously and leads to change. It’s the school stopping the practice of ‘epistemicide,’ which is the killing of our knowledge systems. It’s the school looking at us through a decolonizing lens and, above all, understanding and practicing the process of decolonizing knowledge. Understanding that in quilombola, Indigenous, and riverine territories there is knowledge that must also be validated. When the school begins to understand these knowledge systems, it begins to truly listen to the individual who is trying to be educated. When it recognizes our knowledge as a legitimate part of the curriculum and not as a curiosity, it becomes a territory of healing.”

Anti-racism and mental health

“Caring means the school being actively anti-racist; it means understanding that my mental health is intrinsically linked to respect for my culture, my land, my history, and my people.

Talking about mental health today, in a historical process, means understanding that every day we experience erasure within our school institution — erasure of our feelings, our voices, and our sense of belonging.

The experiences that work are the ones in which we can take on real leadership. Like the student councils, but truly autonomous councils that discuss public policies, that give opinions on rules and on the curriculum. Not decorative ones that basically organize parties and musical meetings. We don’t want to be just event planners; we want to be recognized as people with a voice who deserve respect.

Real belonging comes from a deeper place, from co-responsibility — meaning when young people can also exercise responsibility and decision-making roles.”

Ancestrality without folklore

“A concrete experience of belonging is when the school opens its doors for the elders of our communities to teach; when my grandmother’s wisdom is treated as a class, not as folklore.

The school calendar shouldn’t be limited to national civic dates. We don’t want to be objects of study on April 19, the National Day of Indigenous Peoples. Our people, our history, and our knowledge exist all year long. But we are made invisible.

Classes promoted under the law requiring the teaching of Indigenous and Afro-Brazilian studies (Law 11,645, of March 10, 2008) are often folklorized and superficial. It’s so minimal that it becomes almost trivial.”

Adult-centrism

“We need to name the barriers that make us ill, because there’s the whole issue of inequality, violence, and the precariousness of the school environment. Beyond that, there’s adult-centrism — that belief, often unconscious, that adults know what’s best for young people. We’re invited to participate, but never to decide. We’re supporting characters.

Another important issue is tokenism — when the school calls an Indigenous, Black, or LGBT youth just to take a photo and say ‘we have diversity,’ without giving real power. We’re only invited to validate, to fulfill a diversity quota, never to discuss public policies on diversity. This barrier is violent and reinforces institutional racism.

For many Indigenous and quilombola youth, school is the first territory of violence, the first place where they experience racism. In elementary school, I was only remembered when I had to participate in the civic-military parade and wear my Indigenous regalia — to be exoticized and made to represent 1500.

Throughout my schooling, I only saw representation of my people in lectures when I entered high school and reactivated the Neabi (Center for Afro-Brazilian and Indigenous Studies) at the campus where I studied. That was when we were able to organize a lecture on the importance of affirmative action.”

Collective protagonism

“I grew up being made invisible on a daily basis. And this still happens in our schools. I went through a process of mental and social suffering due to a lack of representation, because I didn’t feel welcomed by the teachers themselves.

Young people need to be part of a council. One example is the direct vote for student representatives on school boards, as happens in some federal institutes. This creates real representation and leadership. And when we talk about leadership, it’s important to remember: in traditional communities, leadership is not individual — it is collective. It’s not about creating a ‘brilliant self,’ but about forming agents who care for the community.

The school needs to trust in our ability to care for ourselves and for our peers.”

Racial literacy

“Any mental-health policy will depend on our presence to be successful. If we don’t understand the subjectivity of young people, if we don’t listen to them, the state plan — discussed in the course — will fail when implemented. The plan must ensure that student councils and youth committees have real work: their own budgets, belonging, a place in decision-making.

In the Youth Council of the Brazilian southern state of Santa Catarina (Conjuve-SC), the greatest demand from youth is the lack of space. There’s no point in a manager, a 50-year-old adult, proposing youth policies. They may have studied, but what academia says is not what happens in reality. These young people are shaped daily, and this changes our perspectives and understandings.

Besides that, we need mandatory anti-racist training for all educators regarding ethno-racial issues and mental health. Because there will be no true listening if the educator isn’t literate enough to understand our pain.”

A territory of healing

“Lastly, the social role of the school is to prepare us for life. It’s to guarantee an integral, humanistic, and above all anti-racist education. For that, we need to be alive and integrated within the community. The school we want is not a building. It is a territory of healing, justice, and social equality.”

Click here to watch the whole webinar. Carlos’ speech starts in 1h04min.

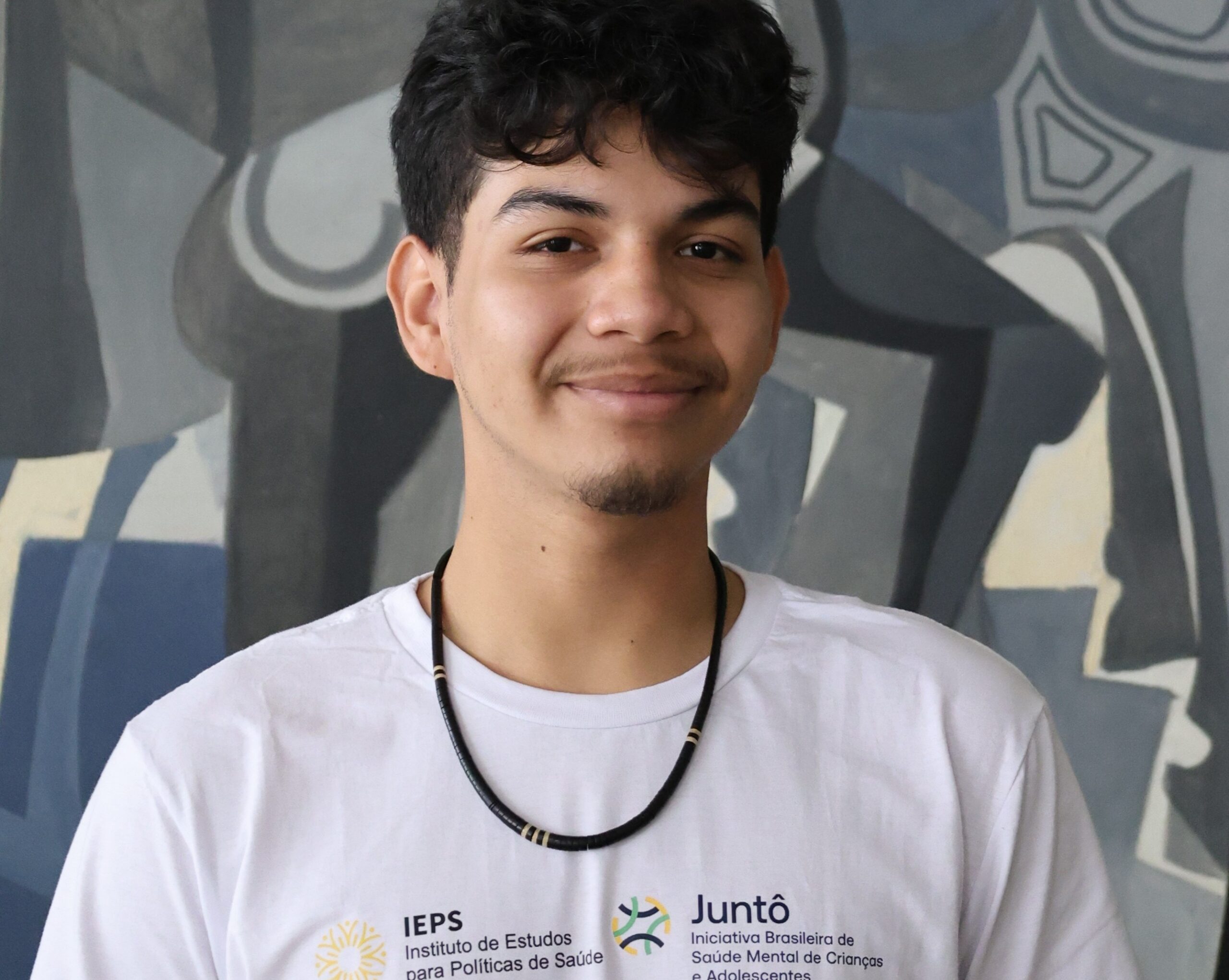

Carlos Ramos de Lima, 18, is an Indigenous youth activist studying Law and a researcher focused on gender, race, sexuality, and their subjectivities in relation to structures of power. He is vice-president of the Youth Council of Santa Catarina (Conjuve-SC) and a member of the Youth Council, a committee maintained by the Institute for Health Policy Studies (IEPS) and by the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Initiative (CAMHI) Brazil.

The webinar is part of the program of the course “From Law to Practice: How to Implement the National Mental Health Policy in Schools”, organized by the Pernambuco Department of Education (SEE-PE), through the EntreLaços Project, in partnership with the IEPS and the Stavros Niarchos Foundation (SNF) Global Center for Child and Adolescent Mental Health at the Child Mind Institute, with support from the Ministry of Education (MEC).

Our Voices

December 15, 2025Do you have a story

or experience about

mental health that

could inspire others?

We’d love to hear your voice!

Share your story with us for a chance to be featured and help others feel less alone.